Title: A Deeper Look at Experience Replay

Authors

- Shangtong Zhang, Graduate student at University of Oxford

- Richard S. Sutton, Professor at University of Alberta

Prerequisites

- Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning (Mnih et al., 2013) [Arxiv] [PDF]

- Human-level control through Deep Reinforcement Learning (Mnih et al., 2015) [PDF]

Accompanying Resources

- Self-improving reactive agents based on reinforcement learning, planning and teaching (Lin, 1992) [PDF]

- Prioritized Experience Replay (Schaul et al., 2015) [Arxiv] [PDF]

- Hindsight Experience Replay (Andrychowicz et al., 2017) [Arxiv] [PDF]

- The Effects of Memory Replay in Reinforcement Learning (Liu and Zou, 2017) [Arxiv] [PDF]

- Time Limits in Reinforcement Learning (Pardo et al., 2017) [Arxiv] [PDF]

Summary

- Experience Replay is the only technique except parallelized workers that allows for uncorrelated data, and thus it has been used in many state-of-the-art algorithms.

- Although most research has used the default size of $10^6$ for the replay buffer, Experience Replay is sensitive to replay buffer size, with huge performance drops for buffers too small or too large.

- The performance drop of large replay buffer can sometimes be mitigated with Combined Experience Replay (CER), experience replay combined with online learning.

- CER is only a workaround, and the Experience Replay is inherently flawed.

1 Introduction

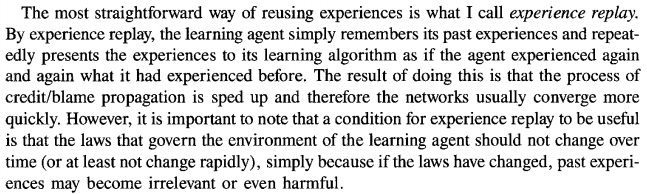

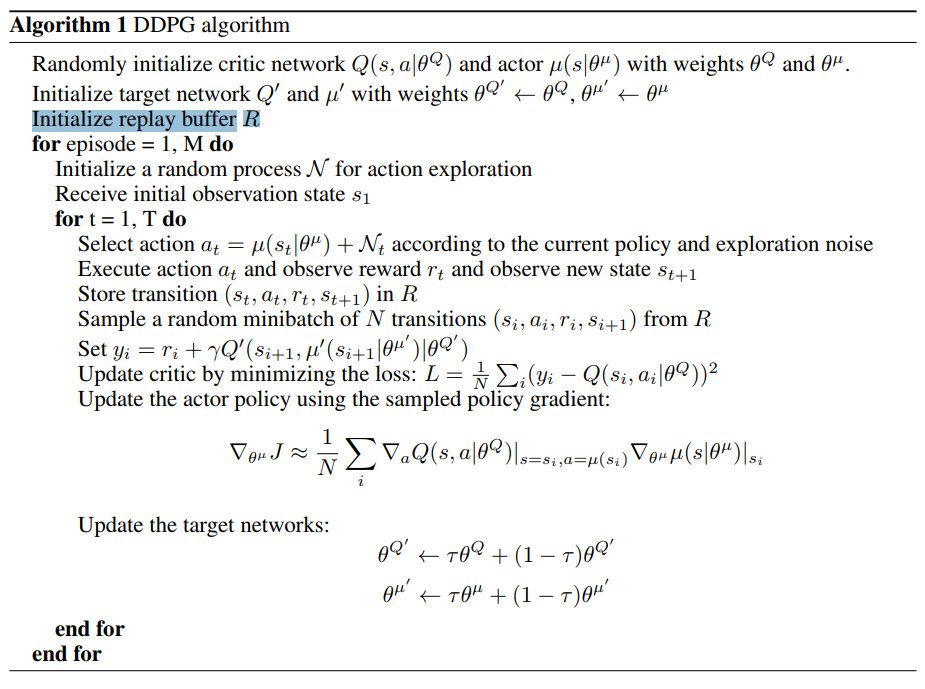

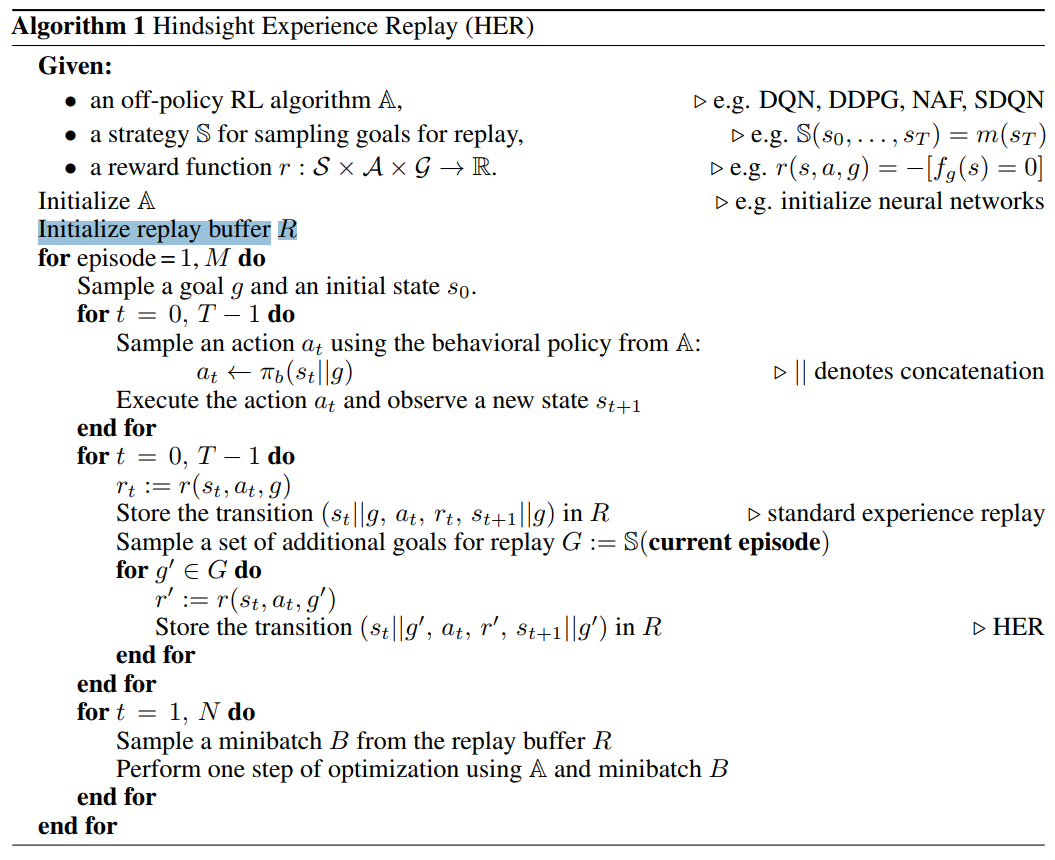

Experience replay is a technique that has been incorporated to many seminal deep reinforcement learning algorithms. These include Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), Hindsight Experience Replay (HER) and all Deep Q-Networks (DQN) methods. The popularity can be attributed to the fact that it is the only method that can generate uncorrelated data for online training. (One exception is using parallel workers, but this is more a circumvention than a direct solution.)

Although experience replay has been integrated to widely different algorithms with different neural network architectures that interact with different environments, its effects are relatively unknown beyond the obvious increased data efficiency. This is because experience replay has been used mostly in deep reinforcement learning algorithms, which tend to be very noisy, disallowing making meaningful conclusions. We show that experience replay also has

Furthermore, in most experiments, the replay buffer was set to a default capacity of $10^6$. This is not a problem if experience replay is robust under such differences. However, as we show in this paper, the size of the replay buffer can heavily hurt the speed of learning and quality of the resulting agent. If the replay buffer is too small, the replay buffer serves little to no purpose. If the replay buffer is too big, the batched samples are uncorrelated, but the agent will learn from the newest experience a long time after.

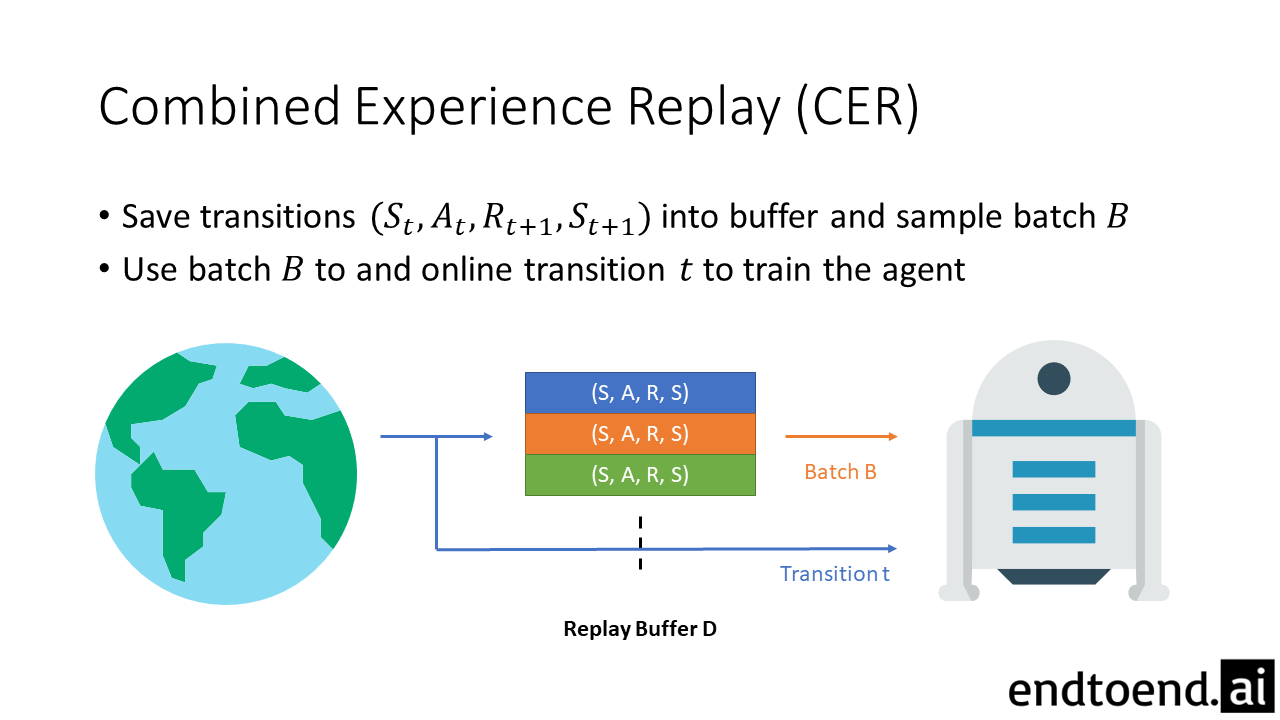

Thus, to mitigate this problem, we combine online learning and experience replay into Combined Experience Replay. At each timestep, the agent learns from a batch that consists of both the immediate transition $t$ and the sampled minibatch $B$.

In summary, we make two contributions in this paper:

- A systematic evaluation of the effects of the size of replay buffer on performance with various function representations

- The combined experience replay (CER) method that makes the algorithm more robust to experience replay size

2 Related Work

There exists another improvement of experience replay called prioritized experience replay (Schaul et al., 2015). In the original experience replay, transitions are sampled randomly with equal probability to form a batch. As the name suggests, in PER, transitions are sampled with unequal probabilities, with “valuable” transitions given higher probability.

Although it is possible to think of CER as a specific case of PER, they differ both in their use. PER was designed to further increase data efficiency, whereas CER was designed to remedy the negative effects of a large replay buffer. In other words, with a properly set replay buffer size, incorporating CER would not have a big impact on performance, but PER will.

We omit the discussion of complexity as we have not introduced CER yet.

3 Algorithms

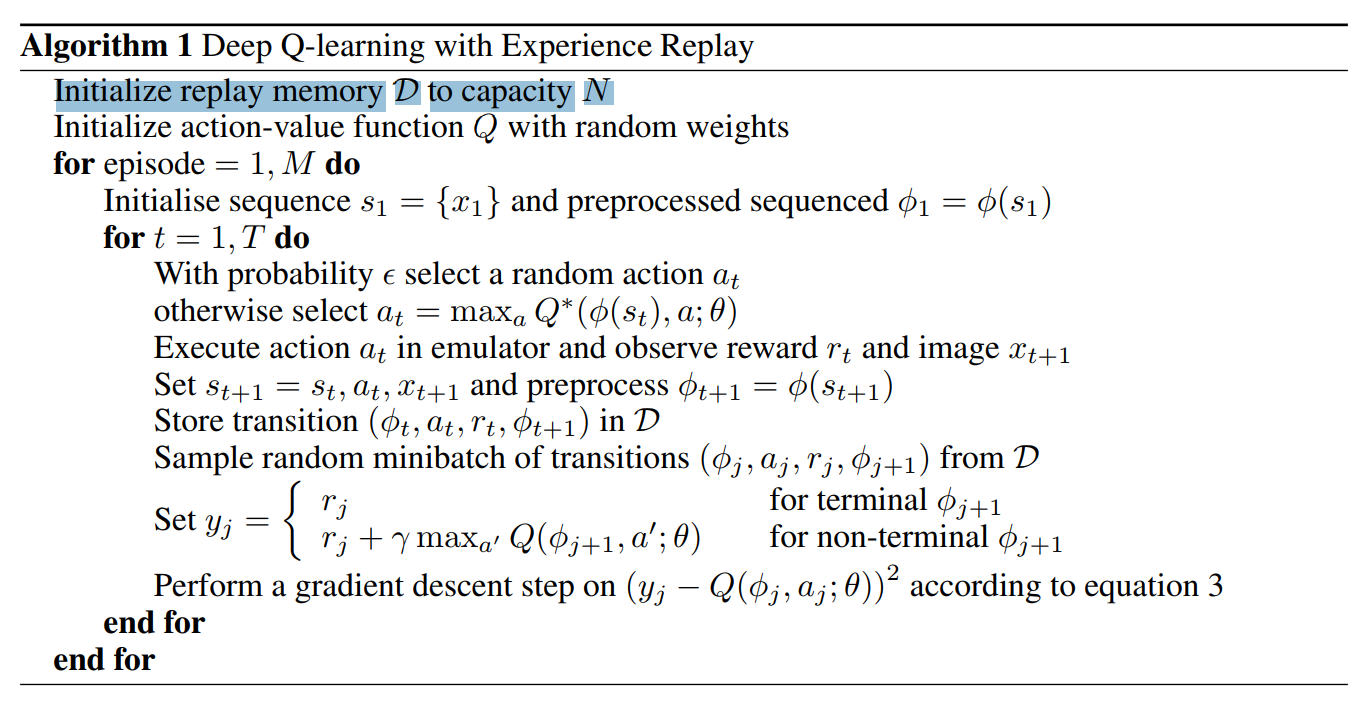

We expect the reader to be familiar with experience replay. Experience replay is the idea of storing previous transitions and sampling minibatches to train the agent. Experience replay by itself is not a reinforcement learning algorithm: it must be combined with another algorithm to be complete. In this paper, we combine it with Q-learning, following the DQN paradigm. Again, we expect the reader to be familiar with Q-learning.

We define three different Q-learning algorithms: Online-Q, Buffer-Q, and Combined-Q.

Online-Q is the online Q-learning algorithm, where no experience replay is used. The agent learns from each transition once and discards it immediately after.

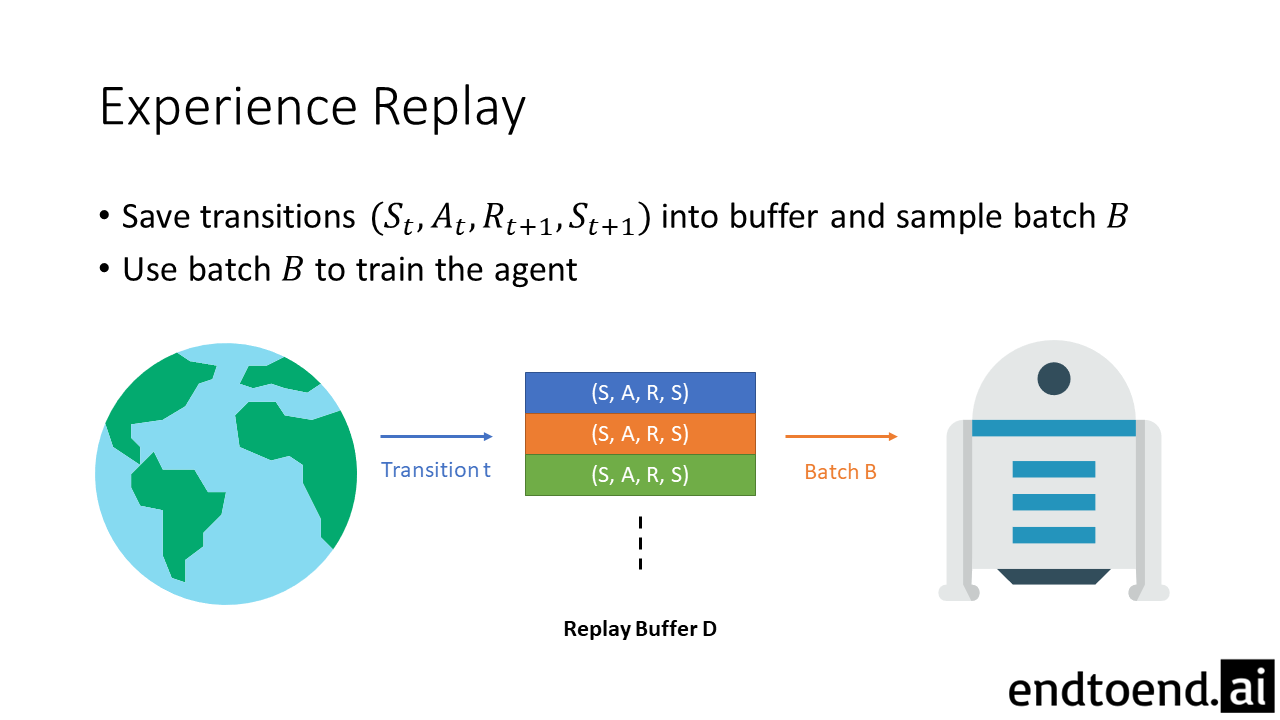

Buffer-Q is Q-learning with experience replay. Every transition is stored into the replay buffer $D$. The agent learns by sampling a batch $B$ from this buffer. This is equivalent to the Q-learning used in DQNs.

Combined-Q is the combination of online learning and learning with experience replay. All transitions are stored into the replay buffer $D$ and sampled for learning. However, the agent learns not only from the sampled batch $B$ but also from the just-experienced transition $t$.

4 Testbeds

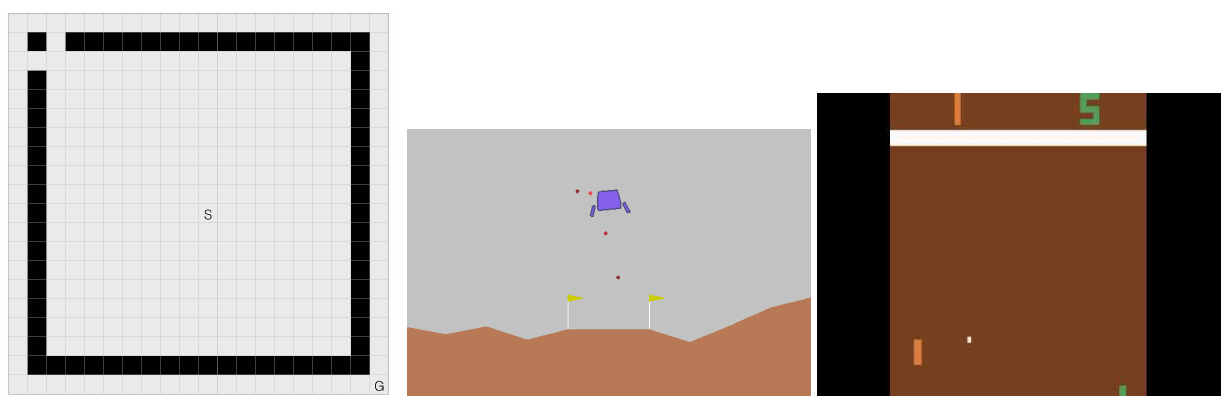

We test these algorithms on three popular environments: Gridworld, Lunar Lander, and Atari Pong (RAM).

In Gridworld, the agent starts at a start state $S$ and seeks to reach the fixed goal state $G$. The agent has 4 actions (1 for each direction), and gets a reward of -1 at each timestep. The black squares define walls, which signify area that the agent cannot move to. If the agent attempts to move to the wall, it will remain in the same position.

LunarLander and Pong (RAM) are well-known environments for testing reinforcement learning algorithms. We direct unfamiliar readers to the official documentation.

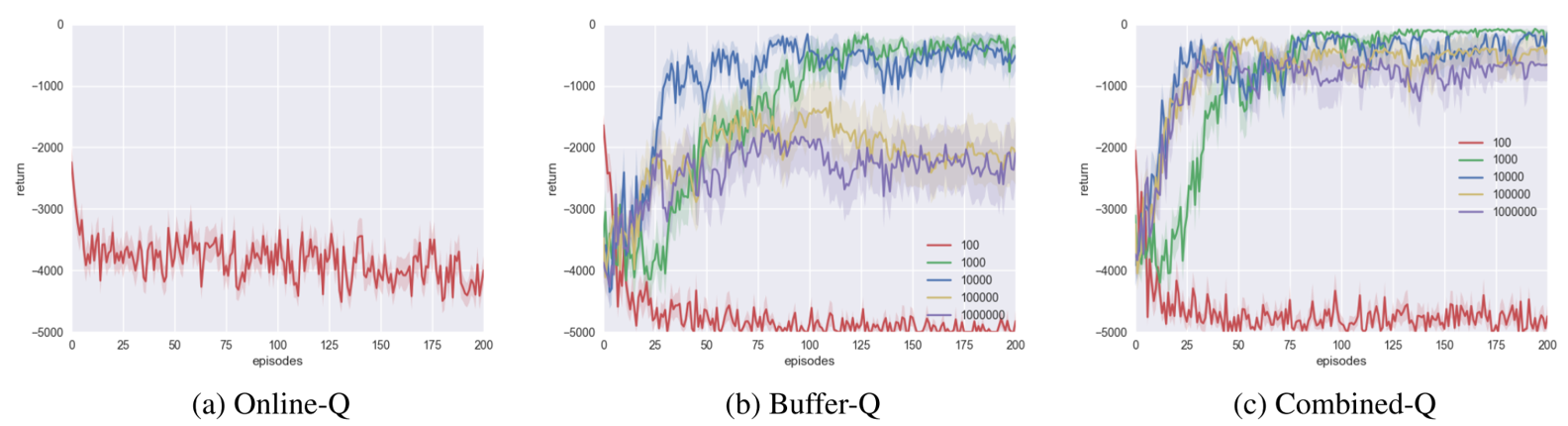

To conduct experiments efficiently, we incorporate timeout in all three tasks. In other words, each task has a maximum episode length, and the episode will end automatically after reaching this length. This is necessary in practice since otherwise an episode can be arbitrarily long. Since this is still a modification of the task, we use a large enough timeout (5000, 1000, 10000 steps respectively) to reduce the influence in our results. To further reduce the effects of timeout, we use partial-episode-bootstrap (PEB) by Pardo et al. (2017).

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Minibatch Size | 10 |

| Exploration $\epsilon$ | 0.1 |

5 Evaluation

5.1 Tabular Function Representation

Tabular Q-learning is guaranteed to converge as long as every state-action pair is visited infinitely many times (along with few other weak conditions). However, the data distribution does influence the speed of convergence.

Only the Gridworld environment is compatible with tabular methods.

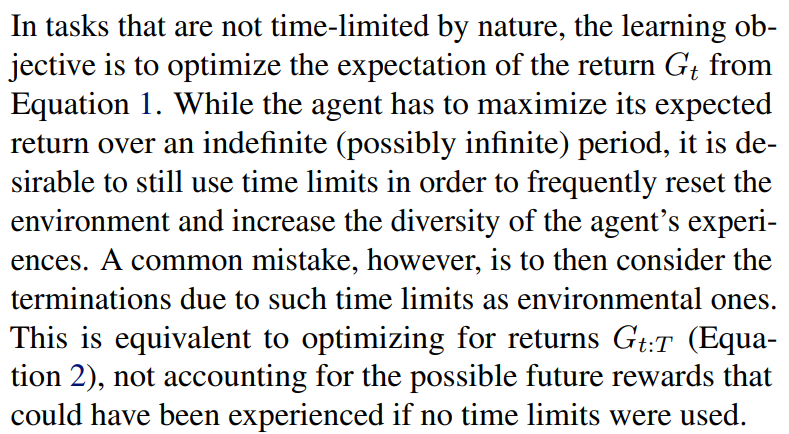

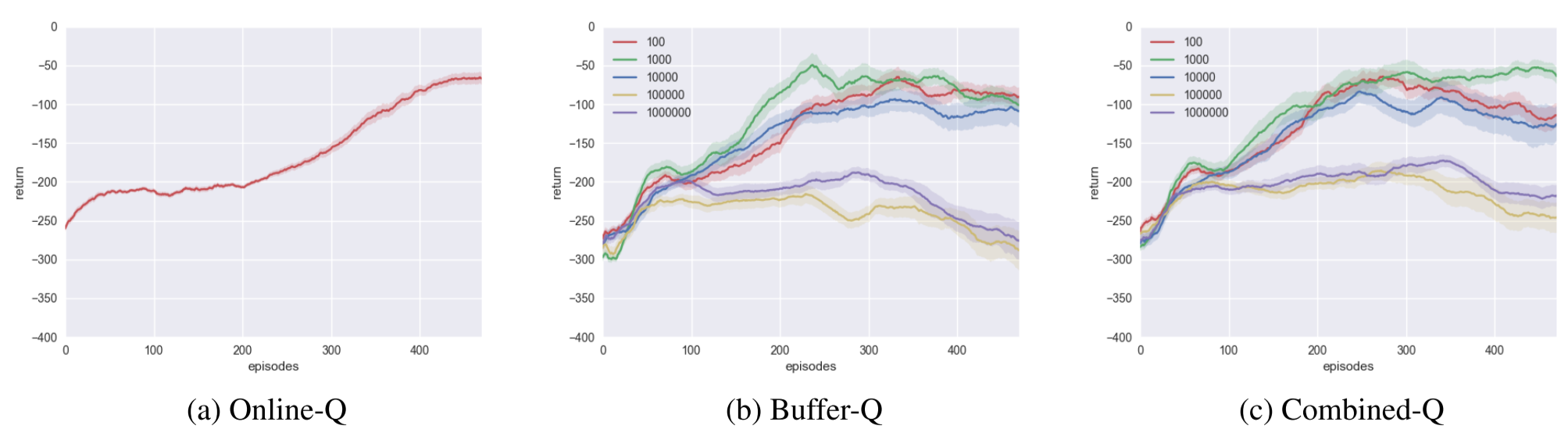

We observe three things:

- Experience replay significantly improves data efficiency. Whereas Online-Q takes 1000 episodes to converge, Buffer-Q and Combined-Q can converge in 100 episodes.

- Buffer-Q performs well for correctly sized replay buffer (100). However, as the replay buffer gets overly large, learning performance drops rapidly.

- In contrast, Combined-Q is relatively insensitive to replay buffer size.

In Buffer-Q, if the replay buffer is large, it is likely that a rare transition that just happened will be sampled later than when a small replay buffer is used. If this rare transition is important, it will also influence future data distribution. Thus, the speed of learning rare transitions can have a compounding effect, shown by the different speeds of convergence for Buffer-Q.

In contrast, in Combined-Q, all transitions influence the agent immediately, so the agent is less sensitive to the replay buffer size.

(We omit the mathematical equation shown in the paper as it is too specific to argue for the general case.)

5.2 Linear Function Approximation

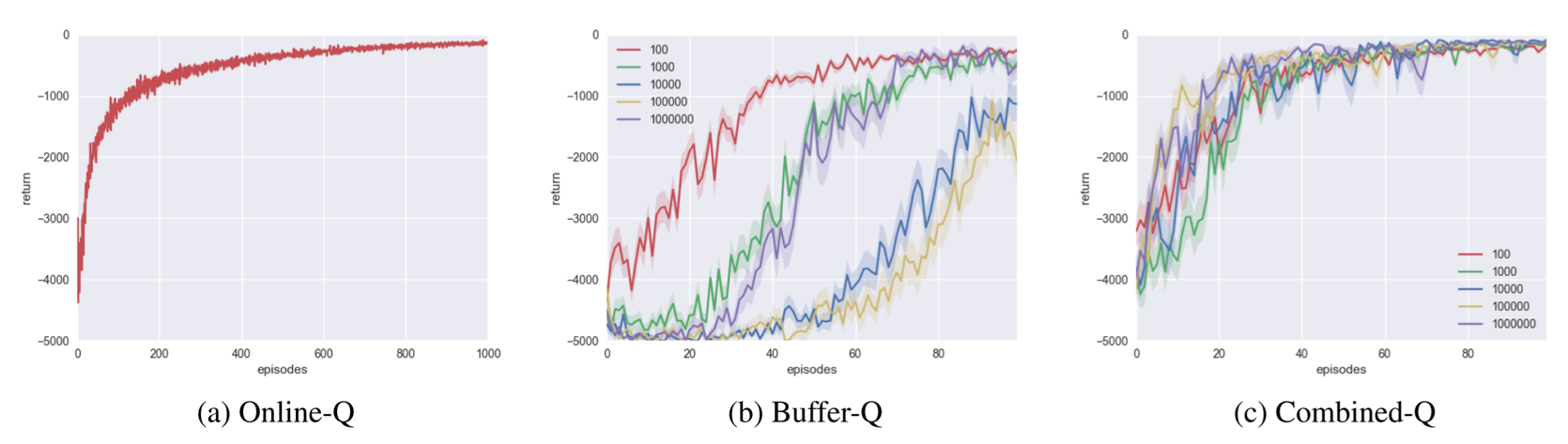

Only the LunarLander environment is compatible with tile coding, the linear function approximator we use.

In Lunar Lander, the state is represented as $\mathbb{R}^8$ via tile coding, and the agent has 4 actions. To encourage exploration, we use an optimistic initial value of 0 by initializing all weight parameters to 0. The discount factor $\gamma$ is 1, and the learning rate $\alpha$ is 0.125.

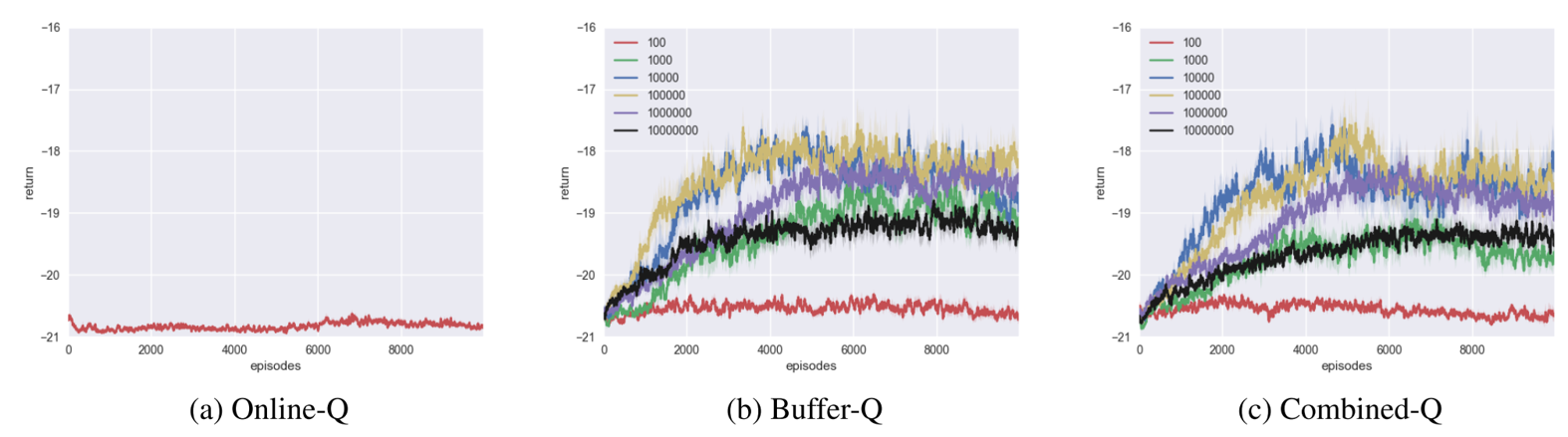

Again, we see that Combined-Q is more robust than Buffer-Q for non-optimal buffer sizes.

5.3 Non-linear Function Approximation

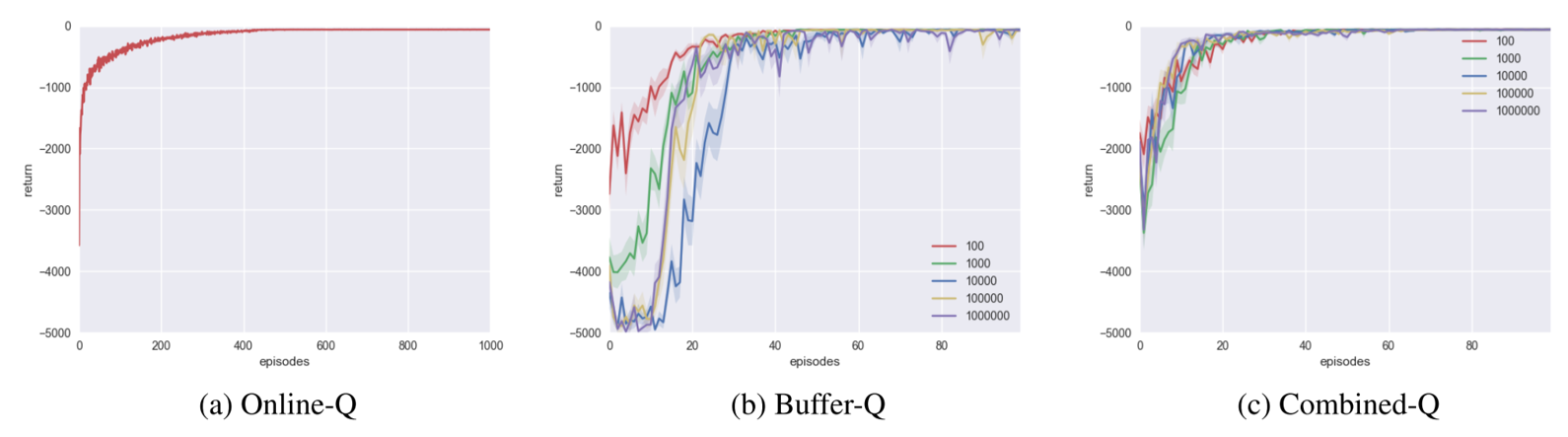

All three environments are compatible with nonlinear function approximators. With Gridworld, the states are encoded as a one-hot vector.

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| # of hidden layers | 1 |

| # of hidden units | 50, 100, 100 respectively |

| Optimizer | RMSprop |

| Initial learning rate | 0.01, 0.0005, 0.0025 respectively |

For Gridworld, the agent fails to learn with Online-Q or Buffer-Q and Combined-Q with buffer size $100$. It seems that the network seems to overfit to recent transitions if the replay buffer is too small.

For Buffer-Q, the optimal replay buffer size is $1000$ or $10000$. We hypothesize that it performs better than either extremes ($100$, $1000000$) because there exists a tradeoff between data quality and data correlation. If the replay buffer is too small, the data is highly correlated. If the replay buffer is too large, the data is likely to be outdated.

Again, Combined-Q speeds up learning for extremely large replay buffers.

For Lunar Lander, Online-Q agent and small buffer agents perform well, with Online-Q agent achieving highest performance. This suggests that the function approximators generated by tile coding is less prone to overfitting recent transitions.

Interestingly, many buffer-based agents have a performance drop in the middle of learning, regardless of the learning rate. We attribute this performance drop to the agents overfitting to the task.

For Pong, none of the algorithms learned a successful policy.

6 Conclusion

Although experience replay has shown great success, its flaws have been hidden due to the complexity of deep reinforcement learning algorithms. We identify one such flaw, and show that it can be controlled by tuning the replay buffer size. Prioritized experience replay (PER) is one technique that could address this issue, but it has a $O(\log N)$ even with a optimized data structure. We propose combined experience replay (CER) with $O(1)$ extra computation that remedies the negative effects of a large replay buffer.

However, as the varied degree of success show, we note that CER is only a workaround. The idea of experience replay itself is heavily flawed, and future efforts should focus on developing new data decorrelation methods to replace experience replay.

Final Thoughts

Questions

- The authors claim that CER and PER are different in Section 2. Then, are they modular enough to be implemented together? Will implementing both PER and CER improve or hurt performance?

- The authors claim that timeouts make the environment non-stationary. Why?

Recommended Next Papers